Medieval Convent Drama musicological consultant Matthew Cheung-Salisbury reflects on the recent 40th Anniversary Medieval English Theatre Conference, hosted by the project team at the University of Fribourg:

What if the authorities who prosecuted Jesus and sent him to his death had let him go free?

This question was posed, tongue firmly in cheek, at this year’s Medieval English Theatre conference (the fortieth such conference, organised this year by the Medieval Convent Drama team in Fribourg). A speaker recalled attending enactments of medieval plays in York. Despite the fact that the story they communicated⸺the passion, death, and resurrection of Christ⸺is perhaps the best known narrative in the world from the Middle Ages until the present day, the speaker fantasised that perhaps, this time, the various authorities questioning Jesus in the drama might, just this once, let him off…

What status and function do faithful, repetitive re-presentations of familiar stories have for us, and how did they function for the communities which wrote and staged them, year after year? The presence of METh in Fribourg offered us the opportunity to re-visit these questions in a scholarly way, but also to consider them in practice.

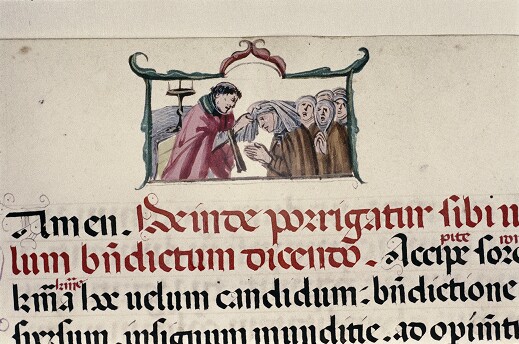

As part of the conference, our brilliant group of musician-actors, directed by Elisabeth Dutton and chorally animated by the inspiring Sandy Maillard, offered to us the first performance of the ludus paschalis which was written by and for the late thirteenth-century Benedictine sisters of the abbey at Origny-Sainte-Bênoite.

This ludus, which depicts the discovery by the three Marys of the empty tomb of Jesus, and the appearance of the risen Christ to Mary Magdalen, comprises texts in Latin and in French and combines several Biblical narratives from the Gospels as well as creative accretions to the Scriptural story.

The Marys, of course, have come to the tomb to anoint the body of Jesus, and there is an exchange with a local merchant who has ointment to sell. All of this dramatic action points to what is perhaps the real climax, and surprise, of the story: that the tomb is empty.

Not a surprise for the spectator, of course, who knows beyond doubt that, the tomb being empty, the next surprise for Mary Magdalen will be the appearance of the tomb’s former inhabitant. But of what merit is the re-presentation, time after time in corporeal fashion, of this epoch-making but universally known story? It is unthinkable that anyone seeing the play at Origny would not have known the central facts of the story, and the diverting non-Scriptural passages are mere decoration for these.

In the words of James Gibson, ‘What really was happening [in the 11th and 12th centuries] when two [people] stood on one side of the altar and sang, and two others responded?’ Our Project team believes that, to consider these questions in anything more than a superficial way, one must enact and participate in these dramas. It is productive, because, like the very appearance of God in human form which anticipates and necessitates the cosmic drama which takes place at the sepulchre, it is incarnational, as Donnalee Dox has argued.

The Origny ludus paschalis is for its players and spectators a corporeal, bodily, perhaps even quotidian (because set in familiar surroundings with familiar faces) realisation of the implications of the Incarnation. To quote anachronistically the Thomistic theology of the sacraments, the players⸺like the priest who offers the sacrifice of the Mass⸺are comprised of both substance and accidence. I was reminded of this when one of the actors, on being asked what he thought he was doing, replied that he was ‘an actor, incorporating a deacon, incorporating an angel’. The enactment of this ludus, for me, is to see the truth of Clifford Flanigan’s argument that the participants and spectators are actually incorporated into the original event: it is a ‘reactualisation or a rendering present of the moment when the archetype was revealed for the first time’: thus, ‘an abolition of historical time’ allowing the members of the community, whether our own or that of Origny, to ‘reactualise’ the past and enter into the past event.

We know that just as every time Christ is condemned in the York plays, the tomb will be empty. But even though ‘no one has ever seen God’ (prologue to John’s Gospel), the re-presentation in living colour of the triumph of Christ over death, for the nuns of Origny and for all time, was, and is, a powerful and immediate medium through which the spectator can enter the same space as the Paschal mystery.

Medieval Convent Drama presents the Origny Ludus Paschalis on two further occasions: on 27 April at the Carmel du Pâquier and on 29 April at La Maigrauge Abbey, Fribourg: